Robert Lumley was born in Southwark, London, in 1920, the elder of two surviving children. The family moved frequently between London and his father’s native Tyneside, chasing work. Young Robert made the best of an itinerant life, joining the Scouts and Southwark Cathedral choir. His father, a blacksmith and carpenter, used to sketch and model for pleasure, but Robert was (as far as we know) the first in the family to paint and draw professionally.

At 14 he won a scholarship to study art at a technical school. Among his contemporaries was the late John Berry.

During the Second World War he served in the regular army, reaching the rank of captain, saw service in North Africa and Italy and fought at the Battle of Montecassino.

Not long after the war Robert Lumley took up an apprenticeship in Cookham, Berkshire, joining a team of British artists being trained to animate under David Hand, art director of Disney’s Bambi. There he met Priscilla (“Sally”) Sidgwick, youngest daughter of Frank Sidgwick the publisher. They were married in 1951.

They settled in Hatfield Broad Oak, Essex in 1952. They set up a business partnership called Broad Oak Studios, providing a great range of services – posters, design work, greetings cards, portraits, children’s wallcharts, animation and (later) ceramics. Robert (“Bob” to almost everyone) became involved in many aspects of local life: footpath maintenance, the village hall, a campaign to oust the headmaster, the first campaign against the expansion of Stansted Airport. Sally became a school manager and was active in church affairs well into old age.

Book illustration had always been in my father’s repertory. In the late 1950s it was rumoured the Beatrix Potter books were going to be “redone” by Enid Blyton. My parents, horrified, bought me a complete set. Alongside it sat a growing collection of John Kenny’s Ladybird Adventures from History, beginning with Alexander the Great and ending with Captain Scott. John Berry’s People at Work joined them one by one.

Robert Lumley’s Well-loved Tales were published between 1964 and 1974. The first, The Elves and the Shoemaker, spent some time at draft stage: half way through, he decided to change the shoemaker from a young to an elderly man. As with subsequent titles, he took great care over the story’s national origins, Germany in this case.

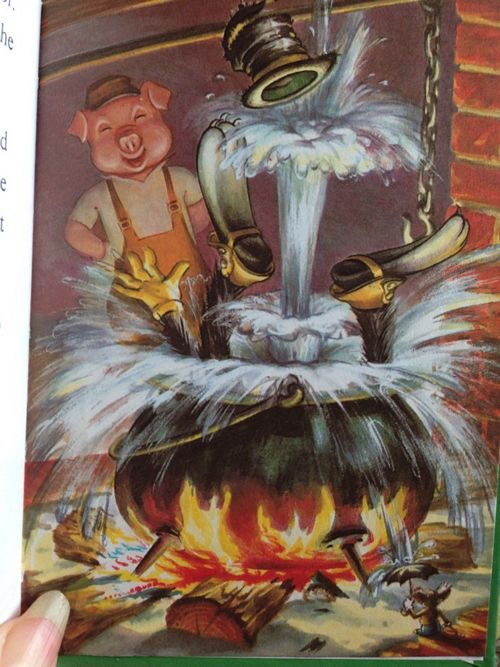

We never gathered what aspect of his work he liked best. But among the most interesting must have been collecting ideas in the early stages. For The Three Little Pigs I was put to work with a copy of The Art of Walt Disney, to find ideas for caricature pigs and wolves. If you know your Disney you’ll see the influence.

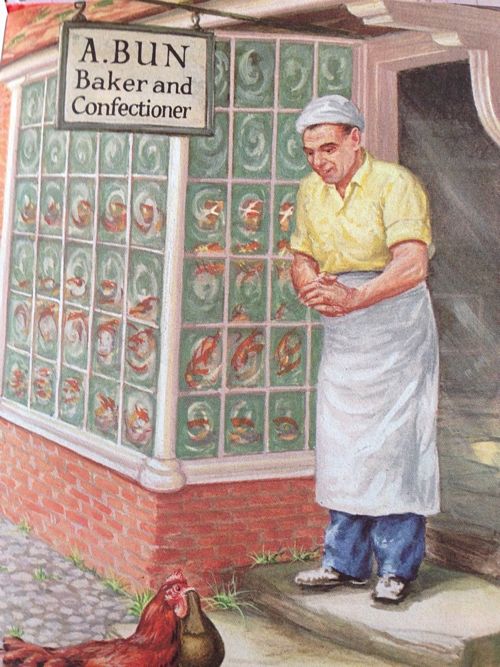

For some reason Robert then kept away from caricature, with the notable exception of The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids. He seemed more interested in real animals, how they moved and behaved, and drawing them accurately. The little red hens were done partly from handsome colour photographs sent by a poultry breeding company, Thornbers. Other animals would have come from a variety of sources.

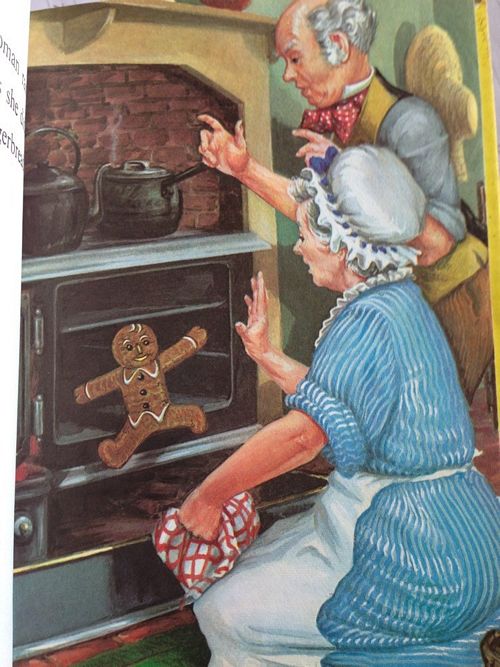

First job with The Gingerbread Boy was to decide what the main protagonist should look like. Eminent cooks in the village were consulted and three prototype gingerbread boys were produced, including a dark one with half a lemon wedge for a nose.

The same book brought a new practice: using local people as models. The old man and woman were local primary school teachers who posed in their own kitchen for a photographer. The look on the woman’s face when she hears the gingerbread boy inside the oven (page 14) is one I remember well from the classroom – it meant something interesting was about to be shared.

The Gingerbread Boy was also the first title to use local scenes. On its front cover (and pages 21 and 23) is a road in Hatfield Broad Oak, the very one where we lived. The book became briefly part of local lore, and when money was being raised for a school swimming pool my father had the idea of selling signed copies. Wills & Hepworth’s unexpected generosity left him with rather more than he had bargained for: they sent 144 copies.

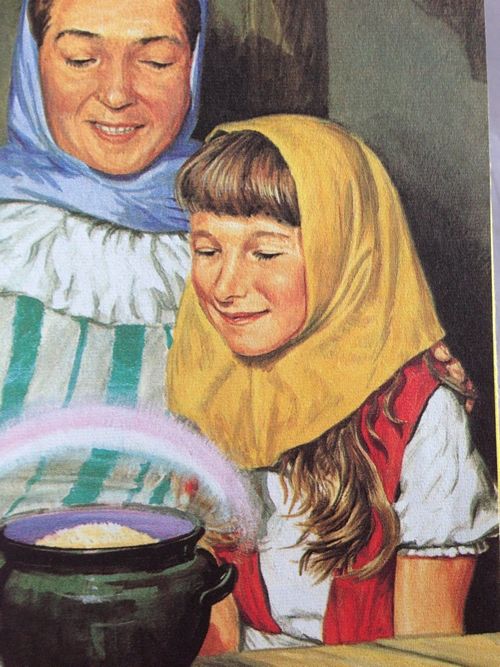

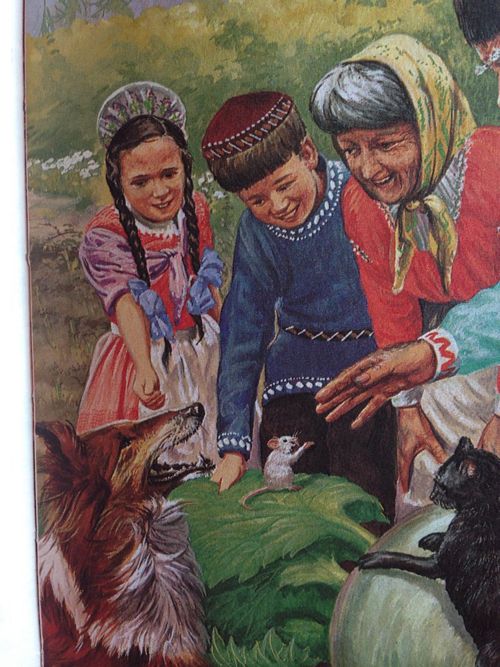

Both practices continued through the series. Obliging villagers were photographed dealing with imaginary hens, pancakes and turnips. Often they belonged to the drama group, and really put their hearts into it (fine examples are in The Big Pancake, The Enormous Turnip and The Musicians of Bremen). Not all the characters look very like their models because of costumes, hair styles and aging.

But for the record… The baker in The Little Red Hen and the Grains of Wheat posed at his own shopfront; the old ovens were his own, but the street scenes are in another part of Essex, possibly Thaxted. [Actually it was the village of Hambledon in Hampshire. You can read more about setting and book here and here]. The exasperated woman in The Old Woman and her Pig was local, and the butcher really was a butcher. The girl in The Magic Porridge Pot still lives near the village. The seven hungry boys in The Big Pancake were sons of (among others) the headmaster, the vicar, a farm worker and the village bobby.

Regrettably the series never launched a steady career in children’s book illustration. Robert was approached now and then and invited to submit ideas. But the only series that might be compared to the Well-loved Tales is a long-forgotten one called The Adventure Book Library, published by Aldus Books and given away with Cadbury’s drinking chocolate. Six titles covered the theme of world exploration, each telling the story of four great explorers. Robert’s three titles were meticulously researched as ever. The other three went to John Berry. The initial business meeting was scheduled a day after my sister’s birthday treat in London; the treat was extended when the boss of Aldus Books, Rad Sidebotham, suddenly invited us all to lunch at Leoni’s Quo Vadis in Soho. Good food and fine wine apparently produced a clear plan and, for once, an exchange of ideas between author and artist.

The same could not be said of the relationship with Vera Southgate. Robert Lumley took an interest in text as well as pictures, and more than once made his own ideas about the storyline known to Douglas Keen. We all laughed at the line in The Old Woman and her Pig: “Rope! Rope! Hit butcher!” Every version until then had said “hang”, and every child who has watched or read Robin Hood knows what hanging is.

But one Saturday morning the script for The Enormous Turnip arrived, and here my father felt he had to act. He opened and read it silently, looked aghast, then read it aloud to the whole family. Imagine our amazement when the mouse turned out to be, wait for it, a cock. Why Ms Southgate wanted to destroy the entire point of the story we never discovered. Happily, as we all know, common sense prevailed.

There were one or two other quarrels. One afternoon I spotted a Ladybird Little Red Riding Hood giving Robert Lumley as the illustrator. Who the real illustrator was we never heard, and I had better not repeat what my father said about the pictures themselves.

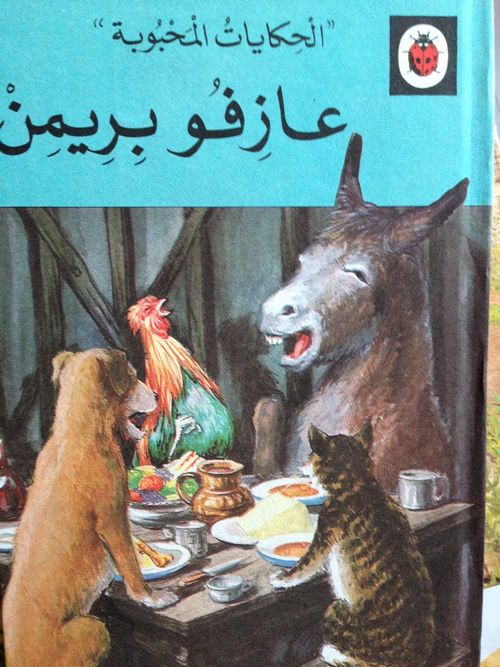

On another occasion, a letter came from a German publisher checking on the granting of permission to reproduce. My father hit the roof, realising Wills & Hepworth had tried to give permission without consulting him. Unfortunately he probably had less hold over the copyright than he thought.Still less is known or remembered regarding The Musicians of Bremen, which gives the illustrators as Robert Lumley and John Berry. The pictures appear to have been painted over in some way, as the style is quite unlike that of either artist. Exactly what happened was never passed on to us. The Ladybird work dried up after the takeover of Wills & Hepworth in 1973. A few years of persistent under-empoyment followed.

Robert Lumley died in September 1976 in a car accident.

The Well-loved Tales stayed in print for several more years. While working in Qatar in the early 1980s, I found the whole series on sale and done into Arabic. I bought them on impulse, showed one to a Palestinian friend and asked what the title was in Arabic. “The Cocky Little Sugar-man” was his reply. Rather less amusing was The Little Red Hen and the Grains of Wheat, adapted to the local culture by having the pig painted over with a crude, two-dimensional sheep, with trotters if you please.

Dear Writer,

I believe that this is Robert Lumley’s son, as you make reference to your sister in this very interesting article. With reference to the Musicians of Bremen, I thought you might like to know that I have the original, signed pastel sketches ( framed) that your father drew of our bantam ‘George’ for this book. I have always thought that the dog was his dog Mitch.

I have very fond memories of your father as he was such a kind and sensitive man to a rather shy little girl. On a school visit to HBO primary school, I remember him explaining to me how he created reflections in water; taking us on wonderful rambles to Hatfield forest and showing me around the studio in his back garden- the mosaic path was wonderful! I still have the signed copy of The Magic Porridge Pot that he gave me on my birthday.

As a family, we all share fond memories of your father, mother and sister, I believe I may only have met you twice, but thought you might like to know that at 55 he has left a lasting impression on me- his sketches of George adorn my wall.

Kindest regards

Cath Cooper( Jones- Vicar Alan Jones’ daughter number 3)

Did your a Mum and Dad have peacocks walking around the garden?

Oh wow what a memorable trip to my childhood 🙂

I was born in the early 70’s and remember all the ladybird books as if I viewed them only yesterday. Being born with the creative itch I found the illustrations so life like and colourful, much better than the illustrations that came after Robert Lumleys magical books. I have only 2 close to my inner child and they are The little red hen and the Enormous turnip. I am yet to come across any of my favourite ladybird books such as …

Cinderella

The Elves and the shoemaker

Princess and the pea

The magic porridge pot

The two that scared me the most was …

Rumpelstiltskin

Billy goats gruff

Most sad but beautiful was by far …

Beauty and the beast.

Now age 49 I am currently creating a journal for my Daughter and granddaughter and Bob will surely be part of this passing on of knowledge and love and creative expression through stories.

Thank you for sharing

Hello!

I’d just like to leave my thoughts if i may.

I was very fortunate as a little girl to have my mum who could ill afford at time’s, buy me and my big sister Joanne a substantial amount of ladybird books. Your Dad’s title’s among my favourite’s.

To this day your Dad’s book’s make me smile and just recently iv’e the pleasure all over again reading them with my five year old little boy who must have me read to him every night ,The Three Little Pig’s, of course! I’m also very grateful to mum for keeping them!

My heart is lifted by your Dad’s art work , my book’s are a real treasure, thank you.

many blessing’s

Wenda and James.

Hi, thanks for this, I have two little girls and I read to them every night “well loved tales”, which I bought off eBay, having remembered them so fondly as a child.

The Elves and the Shoemaker is to the eldest s favourite! She knows the words by heart.

The youngests favourite is the Three Billy Goats gruff, which we act out in the small play area in the local park.

We all really enjoy and appreciate his illustrations it’s so impressive to read about his meticulous method and attention to detail.

Thank you, very much, for the information about “Bob”.

Even after twenty years had passed after the Second World War, families were still struggling to make ends meet, so buying books was at the bottom of priorities for most. Schools were the only source for reading books, and for me, reading time was the best.

Ladybird books were on the classroom shelves, and I must have read all of them. I can never forget how awed I was with the illustrations, and, as at that time, I was greatly interested in drawing, I went back and forth to compare the details!

Years passed without having given thought to the authors and illustrators of those Ladybird stories, but I recently came across a copy of “The Elves And The Shoemaker”, and out of curiosity, checked who the illustrator was. Once I had a name, I could search for him on the Internet, hence this letter.

I would have loved to show my appreciation to Mr Lumley for the fascination that he brought me through his art, but can only pass this on to his surviving family members.

I am now in my sixties, and through “The Elves And The Shoemaker”, I will start reading all of these timeless pieces to my grandchildren. I am very certain that they will enjoy these stories, and, hopefully, have happy memories in the future!

What an excellent article, thanks. Robert Lumley’s illustrations were a joy to look at and complimented the tales admirably. I was saddened to read of his untimely death.

I always loved the Elves and the Shoemaker the most of all the Well Loved Tales…such loveable characters and the perfect fairytale setting. I did wonder why the shoemaker was so much older than his wife though…it’s strange that he didn’t make her older too!

This is a fascinating glimpse into the world of illustration and the challenges your father faced! It sheds light on the complexities of copyright and collaboration, especially during a period of industry change. The mystery surrounding “The Musicians of Bremen” adds another layer of intrigue.

I just stumbled across your site and wanted to tell you how happy I am to have rediscovered some of your father’s work. I’ve been frantically scouring the internet looking for images of the prints I had on my wall as a little girl in the 60s, with searches along the lines of “1960s Ladybird illustrations”

“1960s Ladybird children’s paintings with weaving looms, cotton spools and dye”!

When I finally found what I’d been looking for, it brought tears to my eyes and a lump in my throat- immediately transporting me back to my bedroom with Thelwell pony wallpaper and 2 of your father’s framed Ladybird prints on the wall that used to absolutely fascinate me, such was the imagination and detail…

I didn’t realise he illustrated the Ladybird books too.

What an amazing legacy he has left- what a gift to all children young and old!

Thank you for sharing him and them with us.

(Hope the link works!)

https://uk.pinterest.com/knuckeheadjones/ladybird-illustrations/

Robert Lumley’s dedication to authenticity and local inspiration brought charm to his illustrations. His meticulous research and community involvement enriched his work, making his books a delightful blend of realism and imagination.

This post is a fascinating glimpse into how classic stories get adapted across cultures. The discovery of the Well-loved Tales in Arabic is intriguing, and “The Cocky Little Sugar-man” is an amusing translation surprise. The altered illustration in The Little Red Hen—a pig awkwardly turned into a sheep—highlights the sometimes clumsy but telling ways books are adjusted for different audiences. A great mix of humor and cultural insight!